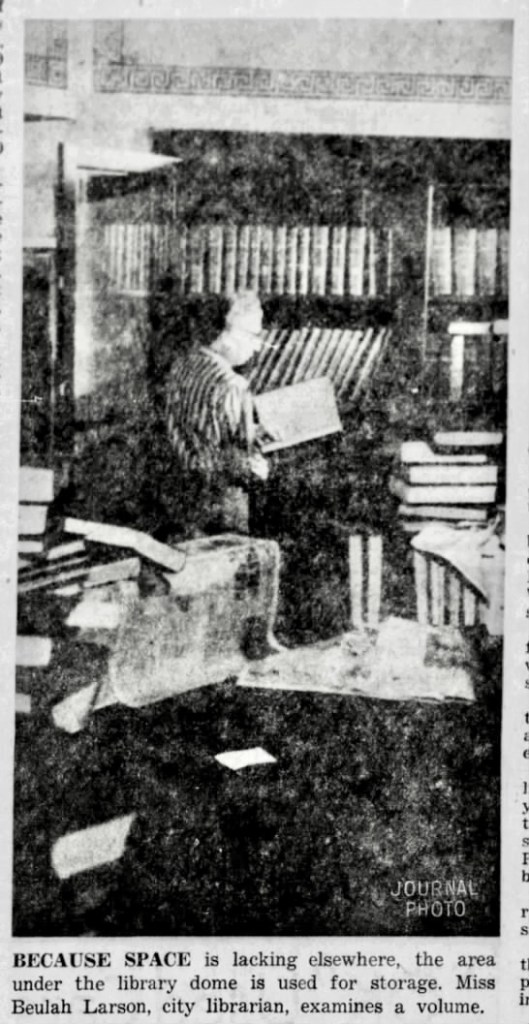

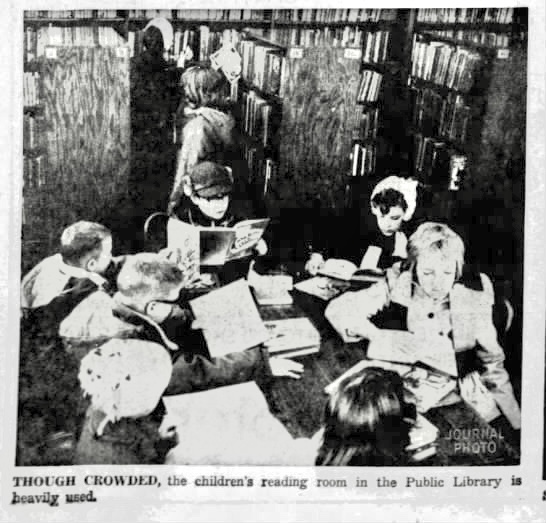

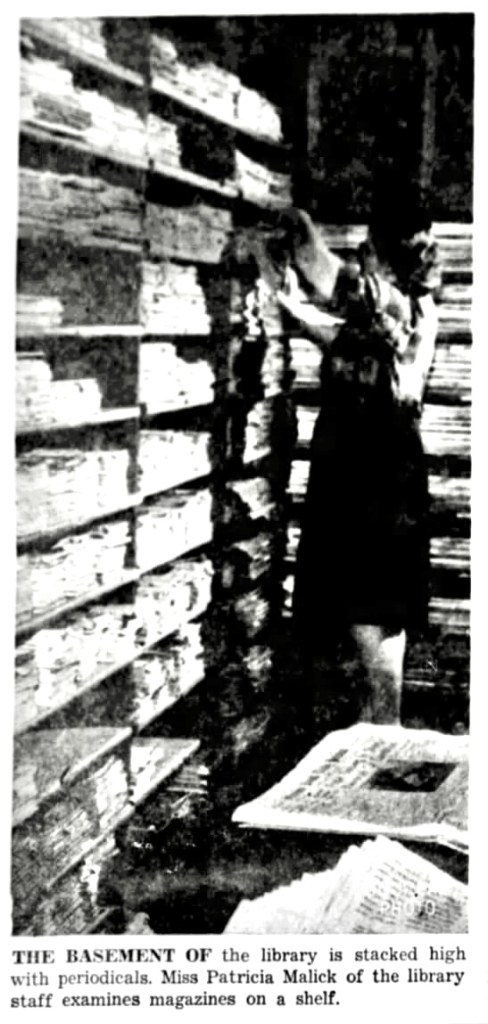

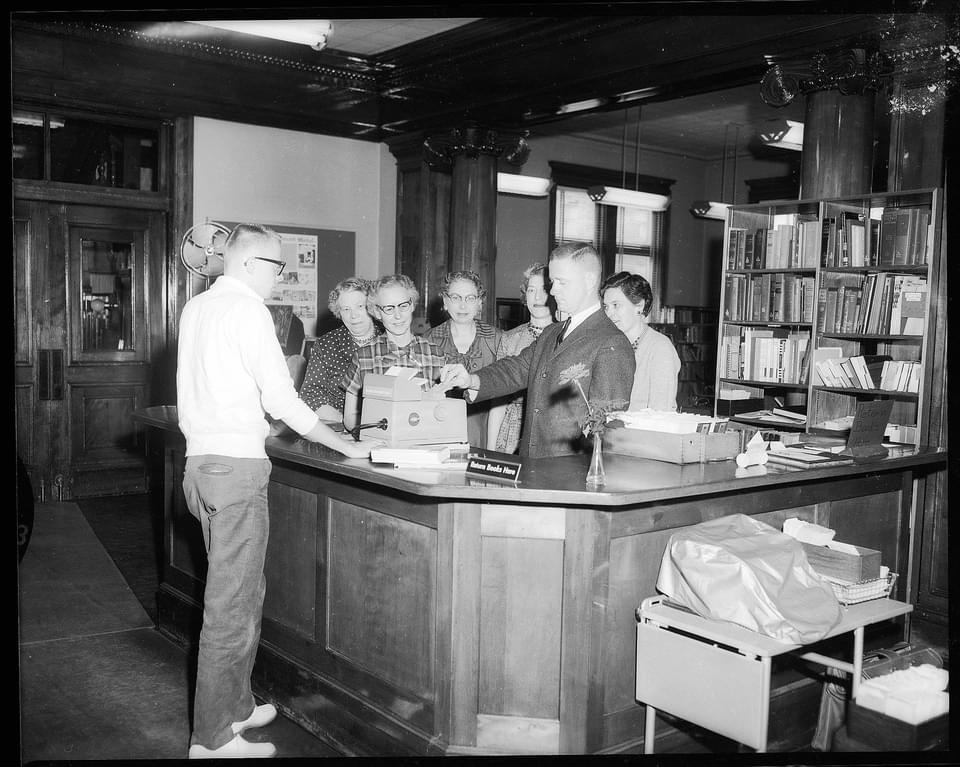

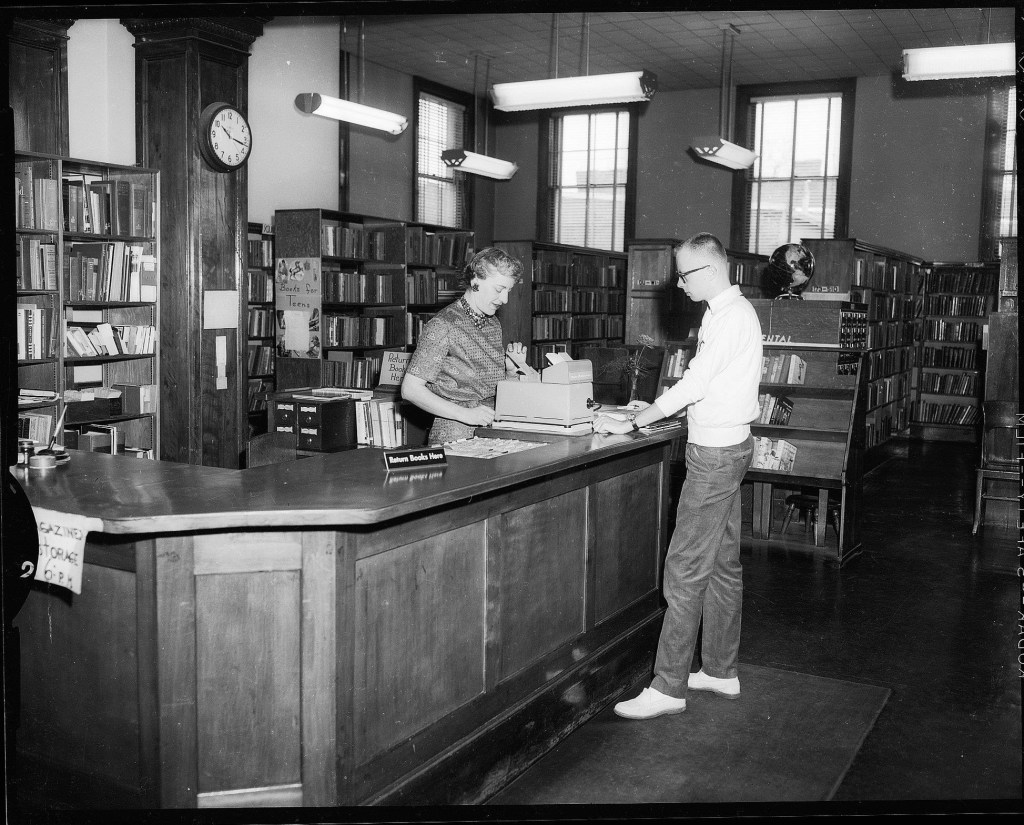

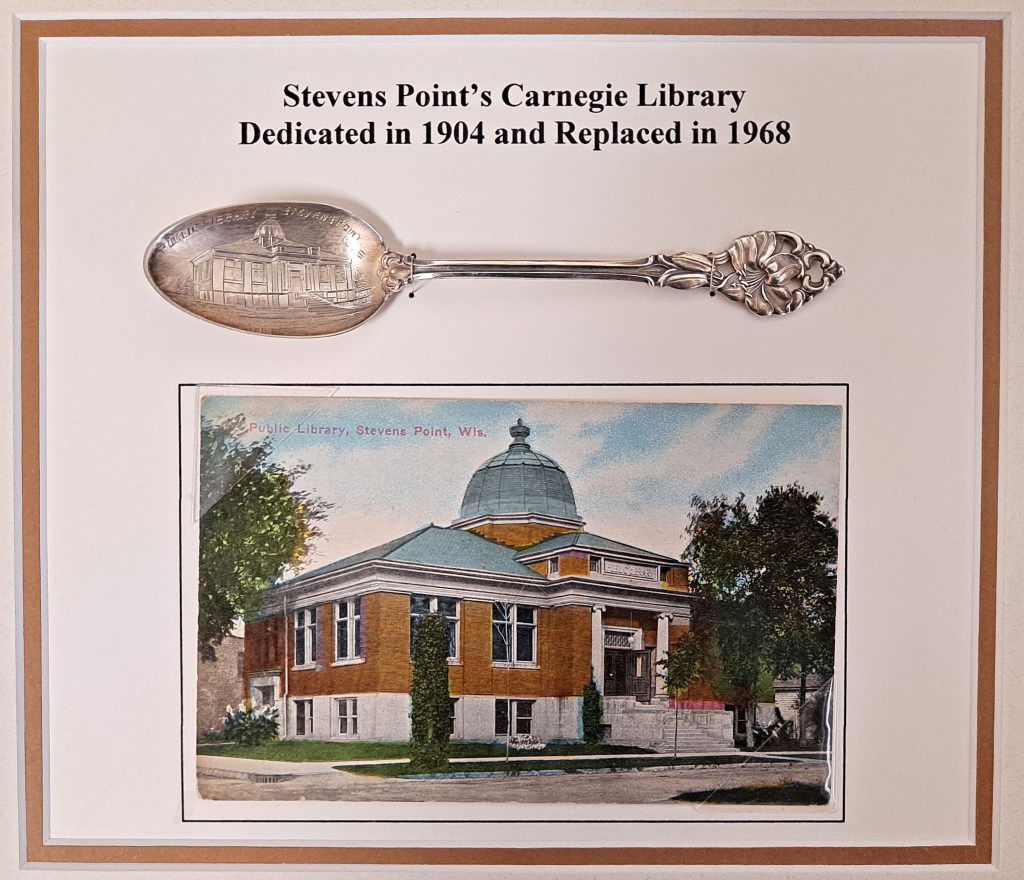

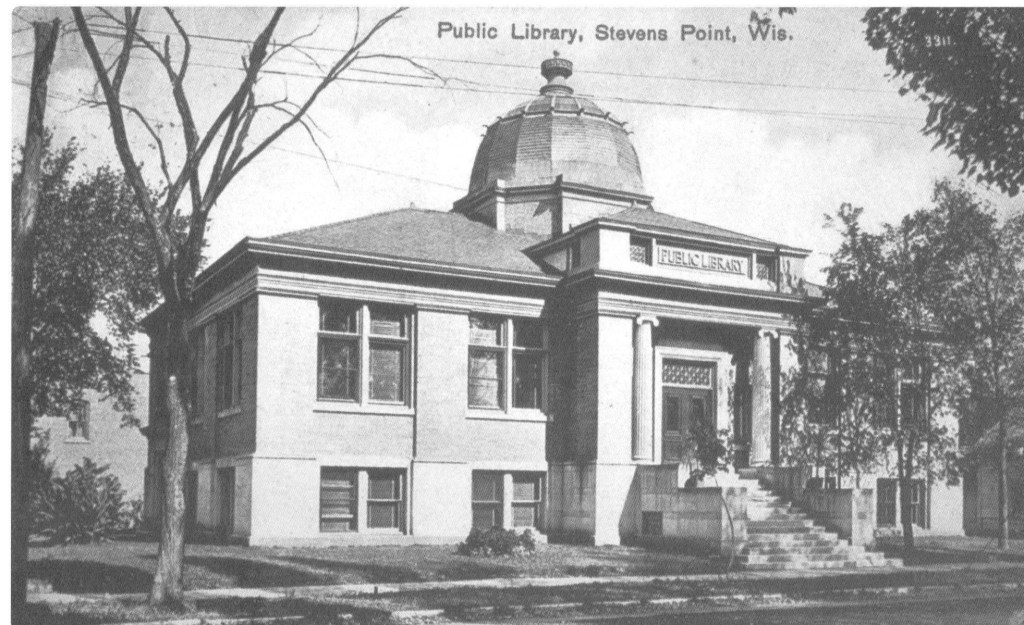

By the early 1960s complaints about overcrowding at the library dominated public discussion. The rotunda once a lovely sight, now called a “bothersome frill” was filled with stacks of bound magazines only reachable through a padlocked gate and the winding old staircase. “Originally, there was an opening in the first-floor ceiling and from the main desk you could look up into the dome. Later the opening was sealed,” and the beautiful special ordered green art glass was covered. Everywhere “book stacks standing where book stacks aren’t supposed to be.” Library officials declared that “the brick structure has outlived its usefulness as a library.”

Complaints of odd angles and no space for growth tabled talk about expanding the original structure. There was a preference to sell the old building and build a new modern library, but funding remained an issue. Then at the end of 1963, Charles M. White died and left $140,000 to the city. His intention was that it be used for a “project or building that will be beneficial” to the people of Stevens Point. Almost immediately it was decided that money would go towards the building of a new modern public library leaving the fate of the Carnegie Library in the hands of whoever purchased the building and land.

In April of 1966 construction began on the new Charles M White library at the corner of Church and Clark Streets, a historic corner where the city’s first church was built in 1853. It was also, ironically, next to where the high school burned in 1892 when the library lost half of its original collection. The new library would be built in the Brutalism style, a steep contrast to the Neo-Classical Revival styling of its Carnegie Library sibling just down the road.

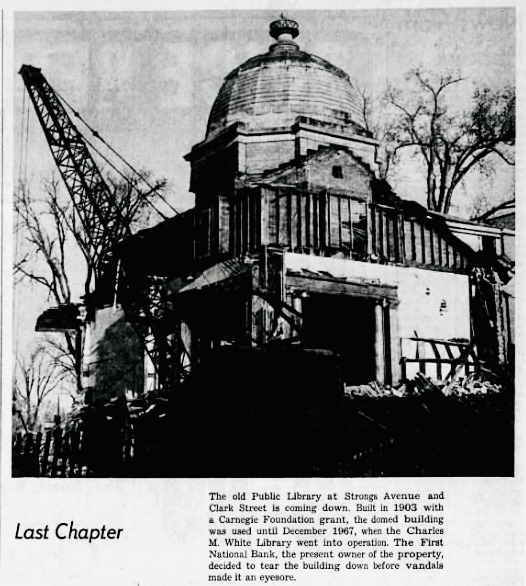

At the end of December 1967, Stevens Points Free Public Carnegie Library closed its heavy ornate doors and prepared for the move. Once again, the immense collection of books moved to a new home just down the block and once again, they found a new home on new shelving leaving the dusty old worn varnished shelves behind to meet their fate.

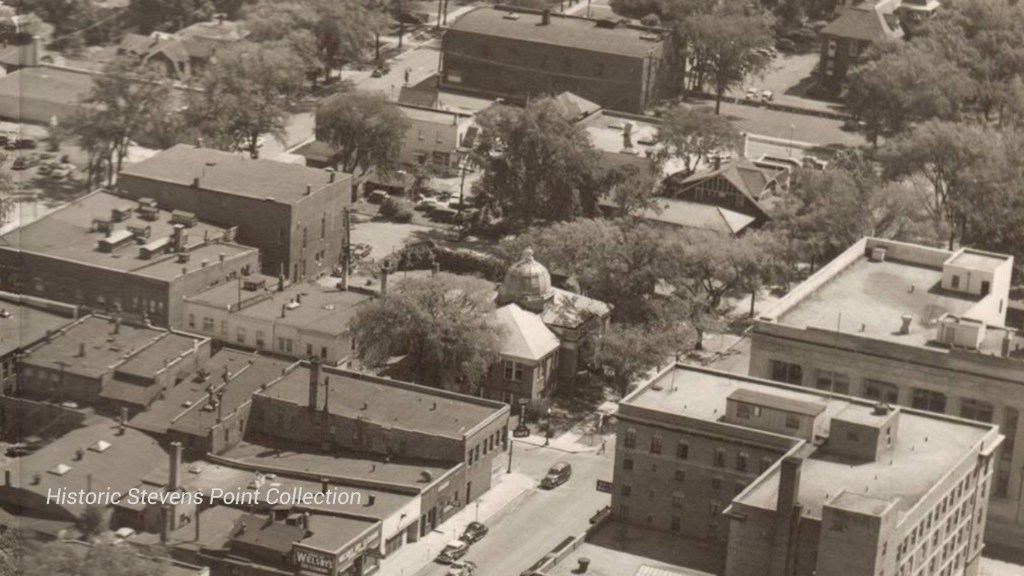

The building was sold to the First National Bank and sat empty for a few years. Then in April of 1969, the bank decided to demolish the building citing worries about vandalism. With that quick decision, one of the most important beautiful buildings to ever grace Stevens Point met its end nearly 65 years to the day of when Dr. Southwick received official word from Andrew Carnegie’s secretary. Nothing would be built on the land again, and today the site is covered in concrete and blacktop.

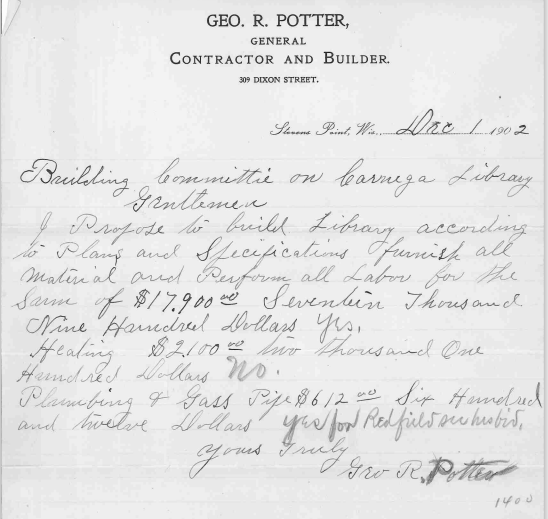

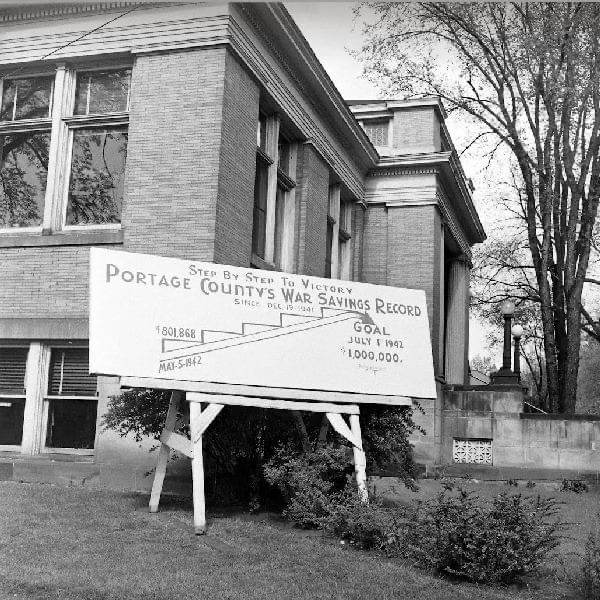

Mike Dominowki photo, UWSP / PCHS Archives

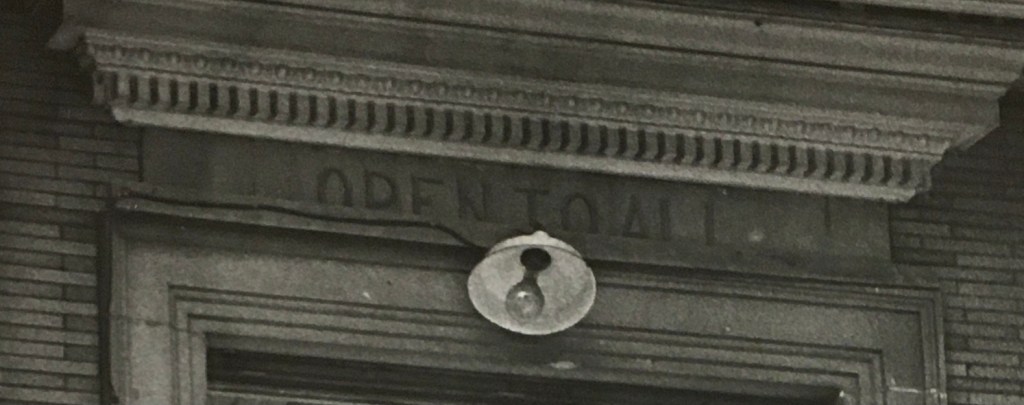

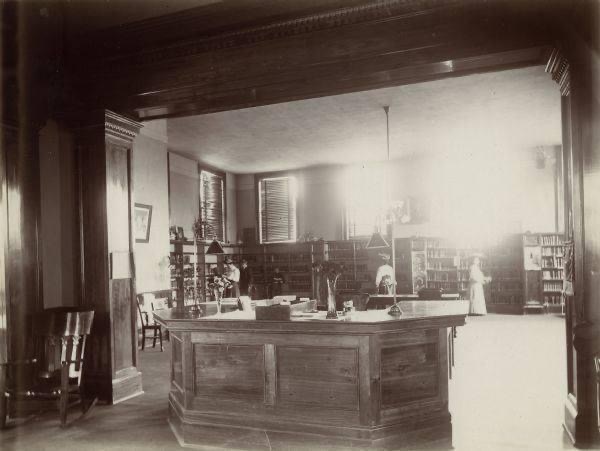

Mostly memories and photos remain, but you can still imagine a bit what it would have been like to walk through the enormous beautiful ornate brass doors of the original entrance. The doors and lamp posts were thoughtfully salvaged by those who realized their importance. Saved by local historian John Anderson and stored in the basement of the Old Main Building at the University, the doors safely sat and collected dust for a few decades. The lamp posts continued to be used and were moved to the front of the new Charles M White Library. Later, the lamp post silhouette was incorporated into the library logo. When the third and present library was built in 1992, the brass doors were dusted off and finally brought out of storage and given a new home. The lamp posts were reunited with the doors over a decade later completing a “new” library entrance and once again, “Open to All.”

The entrance to the Pinery Room meeting space, specifically designed to hold the doors, gave the library a beautiful grand entrance once again. Unfortunately, the transom that hangs above the doors is not original and it is a fabricated replicate based on the door design. Today the original hangs in the home of a private citizen, and at the time was not available for public display. The replica is slightly different than the first transom, but one would not know without seeing the original. Regardless of the differences, the current transom beautifully helps to complete the imagery of literally walking through the doors of another time. You can almost smell the books and hear the creaky floors.

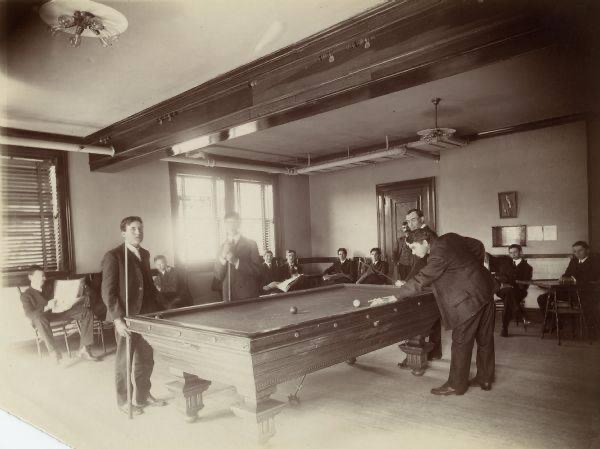

The Stevens Point Carnegie Library is a more than a memory from the past, it was more than a building to many, it was an ideal, open to all, that brought a community together and gave its citizens a beautiful place to grow and learn. Locals today fondly reminisce about the smell of ancient books, the sound of the creaking wood floors and the dark varnished wood. Many do not remember the Carnegie Library, nor know it even existed at all. With only stories and artifacts to share, it is important to keep the memory alive of this lost nearly forgotten building of historic Stevens Point.

We would like to extend our gratitude to Diane Casselberry, Linda Kappel, Bruce Barnes, and the late Wendell Nelson for their gift of information and photos while we worked on this piece about Stevens Point’s Lost Carnegie Library. Without their contribution this article could not have been possible.

Read Part 1 here / Read part 2 here Read Part 3 here / Read Part 4 here/ Read Part 5 here

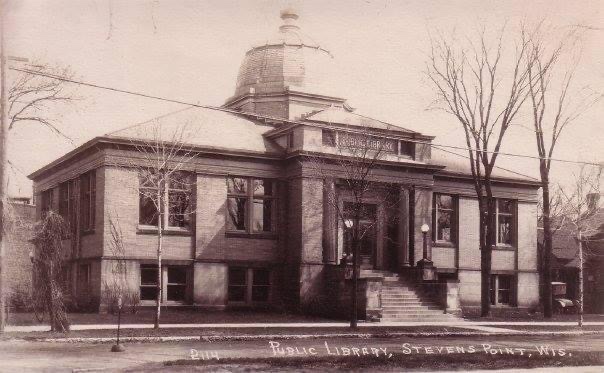

UWSP/ PCHS Archives

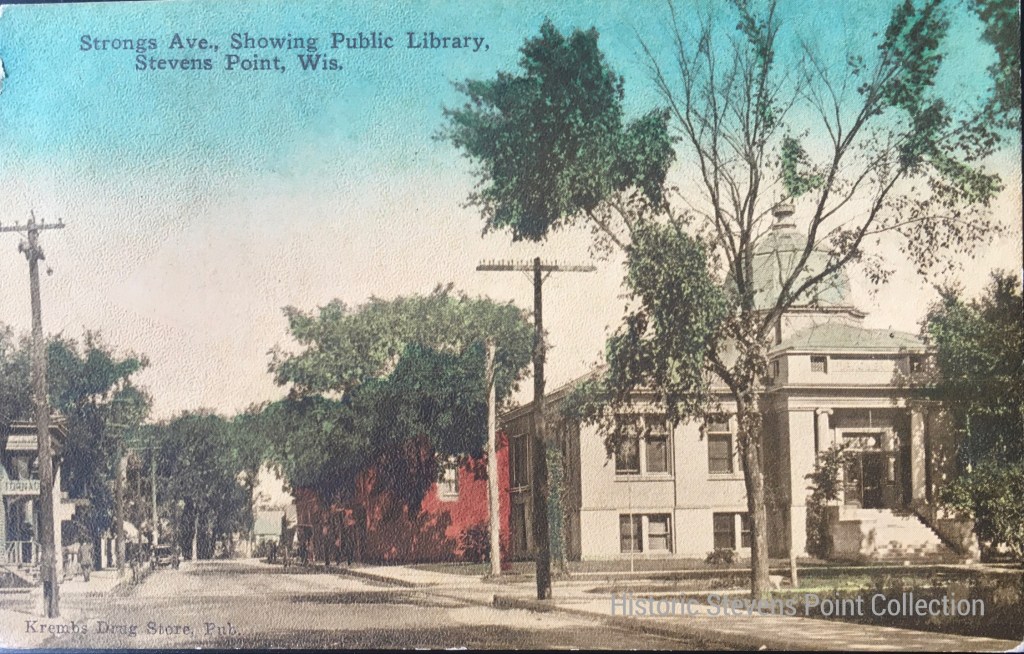

Historic Stevens Point Collection

Sources used over the entirety of this piece:

Stevens Point Daily Journal

The Portage County Gazette

Wendell Nelson Papers

Portage County Library Archives

Wisconsin Historical Society Archives

UWSP / PCHS Archives

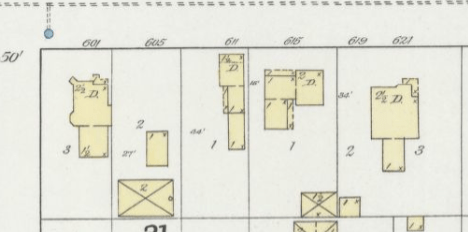

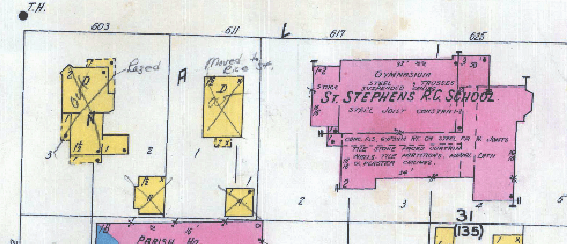

Sandborn Fire Insurance Maps